The Last of the Good Old Puffer Trains

Sir Ray Davies, 80, celebrates Donald Duck, vaudeville, and variety

Notes on The Kinks:

Something Else (1967), The Village Green Preservation Society (1968), Arthur (1969)

Ray Davies turned 80 last week (June 21), so a Kinks jag descended and sucked me right back in. Maintaining your outsider status in rock terms casts complicated shadows, and these albums still dazzle with invention, arrangements, and harmonic surprise. A band both underrated and easy to overpraise, the Kinks suspended Davies on a laconic highwire…

RAY DAVIES EMBRACED an essential British nature wearing an anti-establishment costume. The modern Brit identity has centuries more historical freight than America’s, equal parts pomp and denial, and a peculiarly defensive self-assurance; perpetrators who feel victimized by their ungrateful subjects. BBC announcers even today adopt this smug, paternalistic tone: it frames world events as though the nation held on to its dignity, by God. After a point, rhetorical power was the only fist left to clench.

Rhetorical powers helped Ray Davies create a shapely and seductive alternative world inside his own ambivalence that transcended “alienation” to suggest something more beguiling. He branded “lackadaisical” as its own kind of ambition, and sat quietly, not quite smirking, as Britain’s brittle masks cracked all around him. His better Kinks songs stir your thoughts with tickling uncertainties. “Every day I look at the world outside my window,” he declares blandly in “Waterloo Sunset,” a mission statement in disguise.

Janet Maslin’s surpassing essay on Something Else by the Kinks in Stranded locates this trait when she talks about songs like “Sunny Afternoon” and “Afternoon Tea.” “There’s something benign about all this, something very much in keeping with Ray Davies’s characteristic mixture of longing and revulsion. It’s quite consistent with the idea, in so many of his songs, that life is at its most vivid when seen from a distance…”

Like Paul McCartney, Davies had a fatal case of Music Hall vapors, he lapsed into old-timey schtick often as not, only with more distrust. McCartney fully invests in “When I’m Sixty-Four” but when Davies responds months later with “Love Me Till the Sun Shines” he puts you in the mind of Archie Rice, the washed-up song-and-dance man played by Laurence Olivier in Tony Richardson’s The Entertainer (1956). Rice hates himself and his country more than he can say (backdrop: the Suez Crisis); he would have sung songs like “Holiday” or “Alcohol” with lustful sincerity (see Buster Poindexter).

A lot of this eluded American ears, who blithely dismissed such Davies gestures as novelties, when they actually told you a lot about his sense of history. In addition to broadening rock’n’roll’s palette, these Music Hall motifs reframe the rock tradition to include sentimental entertainment alongside all the rebellion and excitement. They take the place lesser ballads might have, and like McCartney, Davies should have thrown at least a third of these numbers away.

By now Davies’s material sports a classic tinge, its influence considerable. Covers can tell you a lot about a band, a song, and a production. On the mandatory tribute This is Where I Belong: The Songs of Ray Davies and The Kinks (Praxis, 2002), you get the typical polarities, and unlikely triumphs. In this corner, Lambchop falls into the muddy hole that slows “Art Lover” into murky fate. When Professor Elvis Costello sings “Days” as a dirge it brings dishonor to the entire Stiff family. In the other corner, Matthew Sweet makes “Big Sky” into something akin to (forgive the arcane reference) “I Am the Cosmos,” Chris Bell’s great lost Big Star outtake. Round one goes to: Yo La Tengo. Tengo can be considered a cool modern update of the Kinks: suggestive, deserving of a larger audience, far sturdier than first impressions. (Unlike the Kinks, Tengo could release several more volumes of covers and still not fully convey the depths of cultish workship.)

This tribute yields several unexpected yet ideal matchups. When the Jam does “David Watts” it counts among the perfectly matched song-to-band choices, across time, each tapping the universal, ongoing grudge. Same with the muscle Bill Lloyd and Tommy Womack bring to “Picture Book” and Green Day’s “Tired of Waiting,” although it only accents how much Billie Joe Armstrong wished he had been a member of the Lyres. Give me the Fall’s slippery “Victoria” over Cracker’s, but that’s a tough call.

Davies set a gazillion circus mirrors atwirl. Most acts faithfully follow the original arrangements. This means the words, lyrics, melody, and harmonies all rely on a certain pocket of sound that doesn’t work when restyled. Most of these Kinks albums get self-produced by Ray Davies, sometimes with Shel Talmy assisting. The better covers illustrate how much Davies’s arrangements bake in their own production: nobody refers to a “Davies sound,” they refer to his voice, his point of view, and his craft hides behind an embarrassment of clever melodic turns. Two with pedal steel peer out like open secrets: the great Minus 5 do a soaring “Get Back in Line” as the gentlest pop, where “Death of a Clown” from the Williams Brothers whispers of country salvation. Then “Who’ll Be the Next In Line” from Queens of the Stone Age, or “Better Things” by Fountains of Wayne, sound like numbers that inspired their ideal bands.

Then there’s “Waterloo Sunset,” a sacred text from 1968 that nobody should cover, ever, but even if they do, it works out somehow—it’s inviolable. You don’t mind Damon Albarn duetting with the man himself on this track, but he’s inessential and he knows it. This song plays on a giant loop in heaven, in mono, and only for those who know it’s there.

The Kinks occupy that rarefied space where most of their own recordings, even when slapdash, work out as the ideal renditions of Davies’s songs. Exceptions prove this dictum: the Swan Arcade’s dizzy a capella treatment of “Lola” summons more paranoia and compulsion than the original, that fluke hit that bent gender beyond comprehension back in 1970. And Bowie sounds more like Davies than even Steve Forbert (”Starstruck), or Davies himself, when he does “Where Have All the Good Times Gone” on PinUps.

“Waterloo Sunset” plays on a giant loop in heaven, in mono,

and only for those who know it’s there…

But covers can also suggest fantasies: Fastball’s “End of the Day” has a certain punch, but isn’t this a secret Social Distortion song? “Love Me Till the Sun Shines” has a Pavement subtext; “Celloloid Heroes” wants Bette Midler. And maybe the Verlaines, that great lost New Zealand act, went through a time machine back to the ’60s to pose as the Kinks, returning later as an underground afterthought.

Which leads to the question of context: do we distinguish originality mainly through comparisons? Shouldn’t semi-popular acts get judged on their own merits? One line of thinking holds that the band would have been YUGE [sic] if only the Beatles, the Stones, and the Who hadn’t distracted listeners (madness and self-sabotage got the Kinks banned from touring America for four years between 1965-1969). But this discounts the role of uppity kid brother the Kinks indulged: could Ray Davies have played second fiddle so aptly if he’d held center stage? Dave Davies even serves as a surrogate George Harrison figure to his older brother Ray, surging as a songwriter for added flavor. So the context both defines and limits our idea of the Kinks: its live surge in the 1970s seemed like belated rewards (if overshadowed, again, by the Who), and rediscovering the deeper corners of the Kinks catalog signalled rock connoisseurship. The Kinks aren’t like everybody else in that we simply don’t reevaluate other bands to nearly the same extent.

more Kinks

Kinda Kinks: daily updates

Best 50 Kinks Covers: Coverme songs

Americana: the Kinks, the Riffs, the Road, by Ray Davies

The Kinks: The Official Biography, by Jon Savage

The Kinks Kronikles, by Edwin Schlossberg, John Mendelssohn, John Brockman

The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society, by Andy Miller

blowing up: single of the year

Chappelle Roan’s “Good Luck, Babe” was like a Good’n’Plenty box of candied wit even before Sabrina Carpenter covered it last week on the BBC—and made hearts everywhere skip another beat. This crystallized an already glowing moment, creating shimmering colors everywhere, before and after, ever and since. Emerging from her Big Apple at the Governor’s Island festival in New York, and batting supersonic Glenda the Good Witch eyelashes at Jimmy Fallon, Roan now throttles the zeitgeist such that Swifties catch their breath, and Sabrina knew enough to simply hop on for the ride. Following Roan’s arrangement a slower pace, here a cover extended and amplified the original while nestling into its own cozy space. It sounded like an answered prayer, and gave new feeling to all the pent-up anticipation the song harbored. Everything pop can be and more.

And Maggie Rodgers dancing on Instagram.

absolute elsewhere

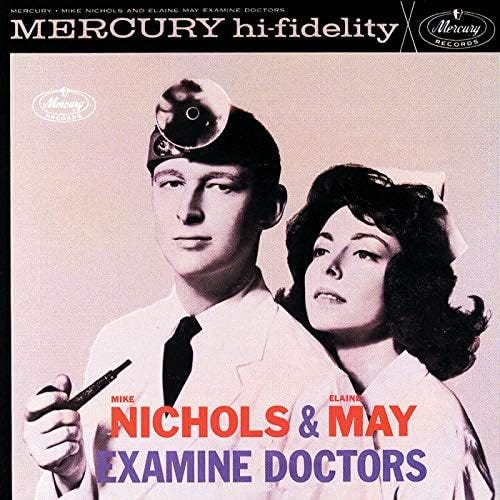

Miss May Does Not Exist, by Carrie Courogen (St. Martin’s Press)

“Heartbreak Supernova,” by Tim Riley, Los Angeles Review of Books, June 25

“There was something almost comedic about the contrast between Elaine the filmmaker and Elaine the consultant, the way a woman who so rarely wrote tight scripts herself was able to trim the fat from the scripts of others, or present one decisive, strategic answer instead of throwing twenty ideas at the wall…”—biographer Carrie Courogen

noises off

Raid the archives for more on why Joe Walsh joined the Eagles (“Worse than coopting a guitarist, the Eagles made Walsh sound tame, which felt criminal…”), and Rob Sheffield’s Solo Beatles List, rejoined, now with comments (from Jeremy Shatan).

“Jesus wears a bracelet that reads ‘What would Mike Pence do?’”—Jiminy Glick

riley rock index: obits, bylines, youtube finds, reference sites, pinterest, beacons.ai, random deep link

Nice one, Tim. And I appreciate that you included the Yo La Tengo set.