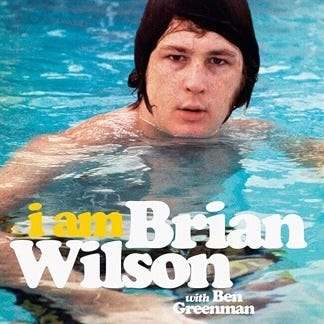

I Am Brian Wilson, by Brian Wilson and Ben Greenman (Da Capo, 2017)

The link between Brian Wilson and Sly Stone, who both died in the same June week, crosses signals with author Ben Greenman, who honors each of their voices in his collaborative books. Both also saw great work fly way too far under the radar, and submitted to drug culture’s various extremities. I covered Wilson’s book for truthdig in 2017, and found it richly understated.

“TIME JUMPS AROUND so much that it’s hard to remember exactly what happened,” Brian Wilson says near the beginning of his disarming new memoir. “Plus, it’s been written about so many times that it’s almost like a story someone else is telling me instead of a piece of my own life.” Wilson, the piano-in-a-sandbox muse who wrote surf anthems for the Beach Boys, contends with both myth and history using his fragile, heartbreaking voice. His bittersweet story joined Bruce Springsteen’s Born To Run testimony atop best-seller lists just as Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize.

Different Brian Wilsons populate his Beach Boys catalog: the teenager who dreams of autonomy in “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” the visionary who caught an era’s utopian ideals in “Good Vibrations,” the lover who proclaims the wisdom of insecurity in “You Still Believe In Me.” And many Wilsons populate overlapping stories of studio antics and drug use, familial pathology and mental imbalance that cloud his past five decades. Most think of him as the looming, bath-robed figure on the cover of Rolling Stone in 1976 that dubbed him a man-child hermit, rock’s teddy bear casualty of too many trips and too much musical genius (“The Healing of Brother Brian”). The Wilson we meet in this book looks back on that mid-’70s caricature with sympathy and dread, and a touch of fondness. As this gentle, over-sensitive voice emerges page after page, a larger picture emerges, and it’s all him.

Dano’s Wilson has an endearing, Pillsbury Doughboy grin, off-angle due to his hearing loss in one ear. This bruised innocence steers Wilson’s narrative.

For the 2014 film Love & Mercy, director Bill Pohlad ingeniously cast two actors (Paul Dano and John Cusack) to play young Brian, intercut with an aging Brian to accent his fractured personality. With his late career surge and this book, Wilson now stands as a beacon of how a style that began in youth redeems its older giants through pop epics like “Smile” (rescued unfinished from 1966’s vaults and completed in 2004).

Movies can’t correct myths so much as reshape them, and Love & Mercy occupies a singular place in rock film: Its dramatization is more truthful than many documentaries, and Dano channels Wilson so artfully his vocal leads on “Good Vibrations” and “Surf’s Up” transcend mimicry. Dano’s Wilson has an endearing, Pillsbury Doughboy grin, off-angle due to his hearing loss in one ear. This bruised innocence steers Wilson’s narrative.

Here’s how Wilson describes the ocean: “I liked to look at it, though. It was sort of like a piece of music: each of the waves was moving around by itself, but they were also moving together. …” And songwriting goes like this: “Songs are out there all the time, but they can’t be made without people. You have to do your job and help songs come into existence.”

The darker figures in his life descend with near-comic force. Wilson’s father, Murray, landed the band its first recording contract, but soon resented his oldest son’s prodigiousness and acclaim. The band rebelled against him in its first year, and fired him as manager. Wilson confirms the once apocryphal story of serving a turd to his father on a dinner plate, which reveals how much rage shaped this naif. Wilson prints a letter his father wrote him in 1965, a chastened tyrant’s clinical business analysis of the band’s new challenges. This conflict, between Wilson and his father, between the band and its earliest champion, portends the later relationship Brian has with the overbearing “psychiatrist” Eugene Landy, who helped launch his first solo album, Brian Wilson, in 1988, where the song “Love and Mercy” first appeared.

Co-author Ben Greenman has captured Wilson’s voice so well every paragraph feels leavened by Wilson’s sophisticated naiveté. Much like his music, his voice hinges on stray insights, hidden corners of self-awareness that salve his mental wounds. As his best music suggests, his keen sense of music history, and deep affection for his brothers, buoy his best thoughts. That he’s the “only” Wilson brother left turns into a recurring theme. “I can get into a space where I think about it too much. I wonder why the two of them went away, and where they went, and I think about how hard it is to understand the biggest questions about life and death. It’s worse around the holidays. I can really get lost in it,” he says.

His love for brothers Carl and Dennis manifests through tales of great vocal tracks and studio bonding (he singles out Carl for “Palisades Park” and Dennis for “Do You Wanna Dance”). And he conveys a bottomless affection for fellow writers, especially when he gets to meet them in person:

Ellie Greenwich came backstage to see me. I hugged her. “Every single day I wake up and thank you,” I said. She looked confused. “You know,” I said, “for writing ‘Be My Baby’ for me.” That’s how I felt that it was just for me. There have been other songs that hit me almost as hard: “Rock Around the Clock,” “Keep A-Knockin’,” “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling,” “Hey Girl.” But it’s hard to re-create the feeling of first hearing “Be My Baby.”

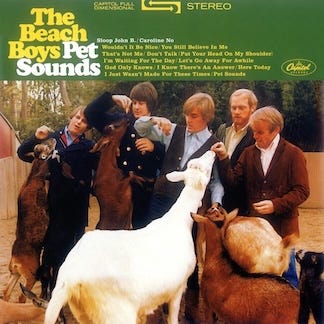

Wilson has no interest in trash-talking Mike Love, the other band member with a memoir this season (pass). In fact, for all the contempt Love ladled on Pet Sounds (with “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” “God Only Knows” and “I Guess I Just Wasn’t Meant For These Times”), Wilson comes off far saner, the victim as peacemaker. A 50th reunion tour in 2014 came off without incident largely because of how Wilson commits to mending fences.

In the vast, spacious canyons of his imagination, where he stashes observations and obsesses about the corniest of records, Wilson spins a miraculous life story from tragic circumstances. Every page pins deathless comments onto music you once thought familiar, like this one about Pet Sounds: “The last word of the album is no [“Caroline No”] but the album is a big yes.”

more

Why the Beach Boys Matter, by Tom Smucker (University of Texas Press, 2018)

Tom Smucker’s guest obit in Robert Christgau’s substack

Daniel Lewis in the New York Times

Simon Rattle remembers his friend to Norman Lebrecht

Tim Page in the Washington Post

Alfred Brendel, 1931-2025

Barry Millington and Imogen Tilden in The Guardian both call Brendel a shameless “intellectual,” and “a musician’s musician,” but as much as I admire his career his recordings never brought enough struggle or exuberance to my ear. How does such “intellectualism” manifest against, say, Pollini—who’s smarter? Do we really care about smarts at this level? Is a Brendel student like Paul Lewis any “less” of an intellectual for all his warmth of tone and grandness of spirit? What makes Brendel similar to Artur Schnabel, his previous generation’s “intellectual”? Why don’t we describe Rudolf Serkin this way—does he have any less formidable ideas about structure? Quotes like this do him a disservice: he “never ceased in his search for musical truth…” Unlike all those other pianists who chase falsehoods.

Of course not, it’s just a way of saying any pianist who can put a sentence together must rank as more thoughtful than some others; it’s silly. He sounds more like a pianist whose scrupulosity works both for and against his better ideas; another way of saying nothing he did inspired me to follow through and read his essays (although “humour is the sublime in reverse” might just tilt things). I heard him play a Mozart concerto once at Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1981, and it had a pearly eloquence; Brendel had the gift of modesty. His recording of Schubert’s B-flat Sonata was my first exposure to the work, and in my mind he helped make it a standard; it’s certainly programmed far more now than it was a generation ago. His upper register could turn glassy, and I wish I heard more of the humor people admire him for. Does it lessen his work any to say I prefer him in more isolated works, like Beethoven’s Andante favori (originally part of the Opus 53, the Waldstein piano sonata)?

noises off

From the archives: Bonnie Raitt, before the Kennedy Center Honors; Randy Newman when we need him most; and The Boys, ineptly titled but still gaining relevance…

“Jesus wears a bracelet that reads ‘What would Mike Pence do?’”—Jiminy Glick

riley rock index: obits, bylines, youtube finds, reference sites, pinterest, beacons.ai, random deep link