Listen to Tim Riley’s narration:

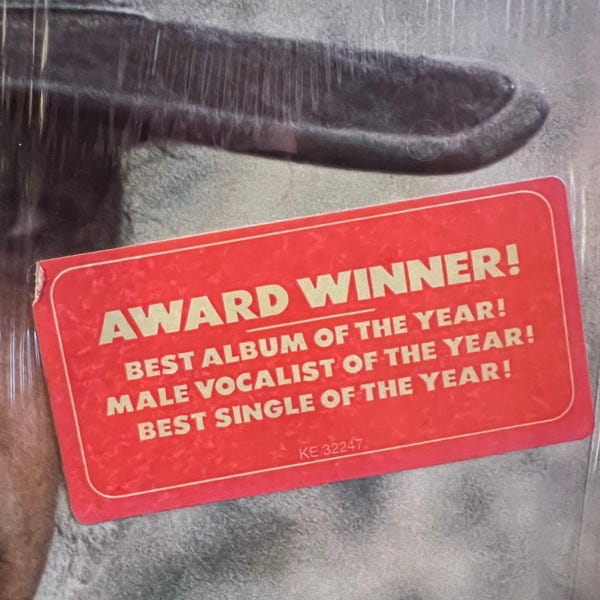

“Behind Closed Doors, Charlie Rich (Epic, 1973)

When I wrote about Charlie Rich for the PublicArts syndication service (now defunct), the dawn of CD remastering had us reconsidering both artistic accomplishment and a new era in fidelity. Certainly, everybody who bought this record in 1973 listened to it on what we now consider inferior technology—like watching a John Ford film on those old TVs. But how can such a detailed engineering reboot yield such so many new ideas about its material? If we listen with more seasoned ears using more advanced technology, how does that boost Rich’s achievement? Or help us hear it as something new, something previously hidden, and inaccessible? Born December 14, 1932, in Colt, Arkansas, Rich would have turned 91 next week. He died on July 25, 1995.

CHARLIE RICH PUSHED hard against everything wrong with the music industry and came to embody everything right with C&W. Fresh out of the Navy in 1956, he played piano for Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis at Sun Studio in Memphis. But once producer Sam Phillips stuck Rich in front of the mike, he never rode the big Elvis coattails like the others. Phillips gave Rich's silken voice his best shot for five years with only modest success, even though rock sage Bob Dylan called Rich his favorite singer. In all, Rich toiled away for seventeen years before releasing this middle-aged country classic in 1973.

C&W has a well-known weak spot for middle-age ennui. But with this quiet breakout, which spent over a hundred weeks on the charts, Rich authored the third-biggest selling album of the '70s. His own heartache was more professional. He had his first hit in 1960, with "Lonely Weekends," but the follow-up, "Mohair Sam," took him five years. This was in part because Rich was a true eclectic, and in part because he was known to tip a few. Behind his closed doors, he seemed happy enough. His bride, Margaret Ann Rich, wrote "A Sunday Kind of Woman," "Life's Little Ups and Downs," "You Never Really Wanted Me," and "Nothing in the World (To Do With Me)," the kind of songs it takes a lover to compose for her husband. Rich's intimacy made a completely different kind of sense when he sang something by her.

You can still hear Rich redeem every country cliché he was so uncomfortable with; his breakthrough, so long in coming, only told him that he’d been on the right path all along…

It took Nashville's Billy Sherrill to ferret out what everybody else was missing, and by then it was 1967. Sherrill had Nashville's golden touch: writing and producing for Tammy Wynette, George Jones, and Glen Campbell. He churned out countrypolitan velour like so much vinyl siding. Even so, it took him six years to score Rich's breakthrough, and then on a number that recast him as someone who found salvation through lust…

also

Charlie Rich’s New York Times obituary by Stephen Holden

The very dated Charlierich.com

Rock’s Back Pages: Charlie Rich archive

Peter Guralnick talks about producing Pictures and Paintings (youtube)

tiny desktop of the month: pj harvey

pj harvey, npr's tiny desk Nov 17, 2023

incoming

There I Ruin’d It, interview coming in January

Jean Knight 1943-2023: “Mr. Big Stuff,” rewired for the big juiced-up-and-sloppy

Year-End Lists (see 2022)

noises off

substack archive, riley rock index: obits, bylines, youtube finds, reference sites, pinterest, beacons.ai, random deep link, got my own RBP oh yeah