The January inauguration has thrown everything into twisted new context: trauma gloat turns prosaic, overstimulation mocks innocence. Suddenly, Severance’s cult of Kier feels cartoonish, like a miniature theme park. The many sex-driven scripts that wrapped in 2024 now feel like quaint throwbacks, and given the cowering media, the confusion-is-sex meme has ballooned in a puff. You can’t play that P. Diddy testimony for comedy, but parsing these soundtracks cues the gap between intent and effect.

#Metoo has already produced some swell movies, like Bombshell, 2019 (an easy target that might have faltered), or Promising Young Woman, 2020 (fierce enough to spawn a backlash), and She Said, 2022 (which almost made the New York Times seem respectable again). But of course, Hollywood’s true nature circles around pulp, and the male gaze reasserts itself despite the relentless impulse to expose taboos. Anora’s Best Picture Oscar accented this conundrum: we root for the emotionally armored professional gal (Mikey Madison), but do we really want her to end up with… a Russian mobster? Any non-rapist will do? These are her choices?

In Good Luck to You, Leo Grande (2022), Emma Thompson honors her desire enough to pay for a male prostitute (Daryl McCormack), and disrobes with disarming physical candor that makes her folly feel like charisma. The quietude of The Assistant (2019) underplays the mundane yet grating humiliations of an office drone (Julia Garner). As the latest Harvey Weinstein trial overlaps with Sean Combs’s freak-offs (rappers vie with moguls in debauchery), the Gods fret at how quickly outrage turns supercilious.

Hollywood’s box office might suggest that the high road to an erotic thriller with a 58-year-old female star lies in tapping a female director-screenwriter (Halina Reijn). Babygirl, a huge streaming hit, plays out a fairy tale about a flush CEO processing some intimate demons by cheating on her saintly husband (Antonio Banderas), realizing some stark truths about the Big Turn-On of High-Stakes Humiliation, and trading corporate success for honest orgasms. It’s so thin and manipulative you’d swear it was written by a misogynist. But no, Reijn, a highly regarded Nordic thespian directs this schlock and shoots for sincerity, even pathos. Disrobing at 58 gets treated as “brave.” In this soap opera it’s more like the shallow characters from Eyes Wide Shut return twenty-five years later for… more of the same phony outrage. And doesn’t Kidman already play some variant of this cliché in The Perfect Couple?

The music underlines the confused messaging. After Samuel (the daunting Harris Dickinson, from Triangle of Sadness) dares Romy (Kidman) with a glass of milk at a bar, Mozart’s Lacrimosa swells up in the soundtrack, because of course a pivot into darkness calls for his Requiem, some algorithm deemed it so. In the scene where they get down to business, INXS’s “Never Tear Us Apart” from 1987 circles the characters, as if that song provides mysterious allure. Oh please: He-Man Michael Hutchence, Model Feminist. Then we get George Michael’s “Father Figure,” that hack 1980s take on dime store bedroom psychology. These choices belie the piece’s forced earnestness.

Because it treats grim situations with whimsy, you take the stakes a lot more seriously, and the characters live with you offscreen—you’d kill for this kind of bracing sanity in the face of death, and the characters seem to live outside the script.

Nobody “understands” much about what turns them on, and kinks by definition confound political correctness. This does not resemble a sophisticated idea. And while everybody deserves their private fantasies, you don’t have to betray a partner to figure out your favorite positions. Reijn presents a false playbook, a completely narcissistic plunge into over-calculated carnality, where risking a family gets framed as the Ultimate Turn-On, and the scene that maps out permission and consent redefines hairy puppeteering.

Gangster flicks put us in high-stakes scenes with low-IQ felons and ask us to sympathize. But what characters do we relate to here? Dickinson’s Samuel intuits what other people want, and he surfs that free-lance dom scene. He’s like a Sex Whisperer—in fact, Romy first spies him calming a mad dog on the street. After some defiantly unoriginal fisticuffs, Banderas’s husband complains, “Female masochism is a male fantasy,” to which Samuel replies “That’s a very narrow view of sexuality, actually.” That’s code for “nobody’s slumming here.” The interaction gets staged as the kid undercutting the husband with wise words of the newly enlightened. This Samuel character moves through these peoples’ lives with impunity, and the husband earns an extra halo because he learns how to bring Kidman to sincere orgasm. The bookend bit reinforces all this: in the “climactic” scene, Reijn crosscuts between Banderas servicing Kidman set against Dickinson in a hotel room—charming a dog.

Does anybody really think betrayal leads to better sex?

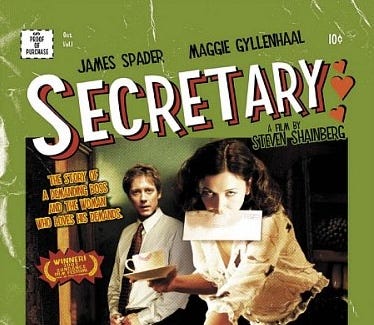

Comedy provides more possibilities, and more embrace. With laughs you get dividends, and less preaching. In 2002’s joyous Secretary, starring Maggie Gyllenhaal and James Spader, sly smiles to the camera juiced up the tension, and a cool understanding of risks draped the encounters. It confused only the right-wing that’s constantly poised for outrage.

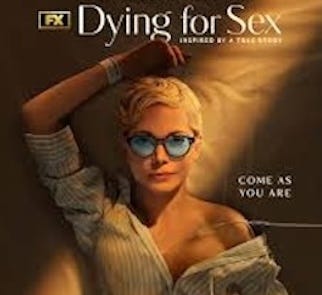

In Hulu’s gut-busting Dying for Sex, Michelle Williams confronts a cancer diagnosis with a hard-won goal: to finally reach orgasm with another person (the script by Liz Meriwether and Kim Rosenstock stems from a podcast memoir from Molly Kochan). Because it treats grim situations with whimsy, you take the stakes a lot more seriously, and the characters live with you offscreen—you’d kill for this kind of bracing sanity in the face of death.

Leaving her husband up front (good move) lands her on dating apps, a hilarious Nice Guy turn from SNL’s Marcello Hernández, and a deepening bond with her best friend, Jenny Slate (human kryptonite). Slate matches Williams for spark and resolve, and the stiff, prim Dr. Pankowitz (David Rasche) even gets a comic arc. The social worker Sonya (the striking Esco Jouley) signals early on her willingness to go past norms, and you sense a synergy of writers, players, and material that recoils at conventional solutions. Williams’s face radiates a complicated clutch of emotions, from sadness and confusion to delight and dismay. Rob Delaney (from that other marvel, Catastrophe) plays her gung-ho neighbor who enjoys playing sub, and the awkward choreography of their encounters enhances their realism, the opposite of Kidman seeking relevance on all fours. Williams’s gleam points this material far beyond Kidman’s glum.

Once again, the soundtrack confirms all your best hopes about clashing emotions: “I Touch Myself,” by the Divinyls, immortalized by Austin Powers; “Girls Just Want to Have Fun,” by Cyndi Lauper; “Rebel Rebel” by David Bowie; “I Will Survive” by Gloria Gaynor, and “Tainted Love,” Soft Cell’s swanky remake of the Gloria Jones original from 1965. Can anyone imagine any Babygirl scene featuring “Girls Just Want to Have Fun”?

Dying For Sex’s final act features an essay on mortality that lends all the sexcapades some earned depth. Do some great movies carry insufferable soundtracks? Sure. Do some great soundtracks get wasted on awful scripts? Of course, although which happens more might make a great social media spat. When these forces blend and set off boomerang flashes, you feel a great team chasing ideas, generating tensions, and making uneasy sense of situations that defy words.

more

Imdb pages for Dying for Sex, Babygirl

Rotten Tomatoes pages Dying for Sex, Babygirl

Metacritic pages for Dying for Sex, Babygirl

Time magazine’s Stephanie Zacharek offers a different point of view on Kidman

Dying for Sex podcast

Molly Kochan’s memoir Screw Cancer: Becoming Whole (Donnie B Inc., 2020)

noises off

From earlier this year: Preston Lauterbach’s riveting Before Elvis: The African American Musicians Who Made the King (Hachette, January 2025): “Like the hint of deism in the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution, Elvis teases the Spirit without delivering an overly heavy dose of God…”

Next month: The Simpsons by Alan Siegel, the Guarneri String Quartet box set, and Bruce Springsteen’s forgotten ticket scandal

riley rock index: obits, bylines, youtube finds, reference sites, pinterest, beacons.ai, random deep link