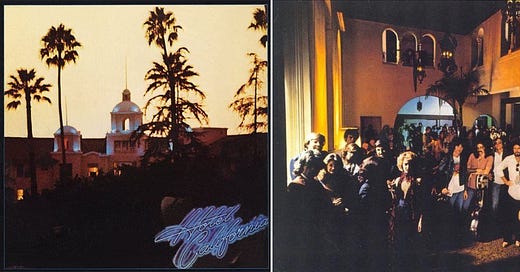

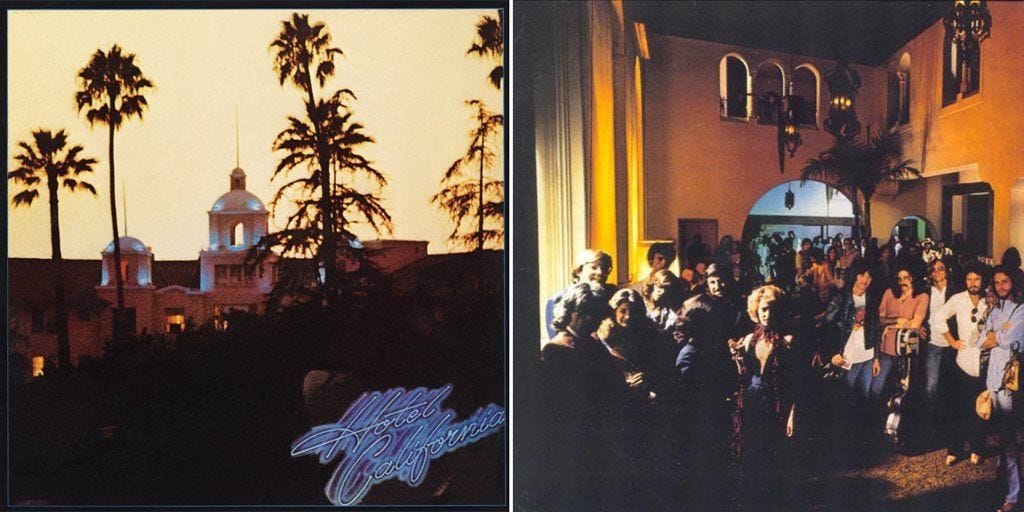

The Eagles, Hotel California (Asylum, 1976)

I liked Robert Gilbert’s “On the Inconvenience of Hating the Eagles,” so I pinged him and asked him why he stopped before Hotel California. We tussled. I wrote up my take, and he wrote up his. Mine runs on his Listening Sessions, here’s my audio:

Robert C. Gilbert responds:

UNTIL A FEW weeks ago, I had never owned, let alone listened to, an album by the Eagles. And in all honesty had Tim not proposed a back-and-forth between us after my piece a few months ago on my Substack about my ambivalence about the group, that would have remained the case. But there I was, going onto Amazon, searching for a CD copy of Hotel California, hitting Add to Cart, and then Proceed to Checkout, and then (did I wince by this point? Yes, I did) Place your order. The next day, a copy of the album was on my doorstep. The jewel box came cracked. Was it a sign? Was I courting doom by giving in to the “cheapest cynicism”?

Hotel California was released on December 8, 1976. As Tim notes, “it felt like pure platinum, one of the first albums to signify platinum even more than Big Statement.” That seems about right even if I wasn’t around back then.

The guitar introduction to the title track, played by Don Felder and Joe Walsh on twelve-strings, was one of the parts any aspiring picker needed to learn, even into the early nineties. My guitar teacher at the time thought so too, and while my barely teenaged mind was set ablaze by getting Eric Clapton’s solo on the Beatles’ “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” down note by note and learning the entirety of Jimmy Page’s part on Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” over a painstaking series of weeks of learning it without sheet music, taking a stab at “Hotel California” failed to ignite anything resembling interest.

By any measure of my musical taste, I should like “Hotel California” as I should also like the Eagles. My favourite Linda Ronstadt album is her self-titled effort from 1972 on which Glenn Frey, Don Henley, Bernie Leadon and Randy Meisner all appear just before they formalized their association as the Eagles. I adore hearing Frey and J.D. Souther, as close to being an official member of the group without ever being one, harmonize on such tracks as Randy Newman’s “Short People” and Joni Mitchell's “Off-Night Backstreet.” I feel a twinge anytime I hear Henley’s “New York Minute.” I love harmony and its sound. I love seventies singer-songwriters and studio pop. I repeat, I should like “Hotel California” and I should like the Eagles.

But then I hear it, and I’m unmoved. It’s a song that has bought wholeheartedly into its greatness. It is to the manor born. It is way too cool for school. Don’t get me wrong, there is a whole lot of musicianship and craft weaved into the six-and-a-half minutes of “Hotel California” but they are stitched into it soullessly.

Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours came out in early February 1977. Seven months later came Steely Dan’s Aja. They, with Hotel California, form a kind of unintended trilogy of persnickety perfection; every note, every rhythm painstakingly in place.

The obsessiveness that underlined the creations of Rumours and Aja is intrinsic to the deep enjoyment of listening to both. The dystopia of “Gold Dust Woman,” for one example, juts up against the almost three-dimensional sizzle of Mick Fleetwood’s hi-hat, the disaffected yet mesmerizing lead vocal by Stevie Nicks, the extravagant objections from Lindsey Buckingham’s dobro, and his deranged cries in the background during the prolonged fade out. It’s a cautionary tale, but one that declaims that debauchery may be regretful, but not in the moment if it sounds this good and sensual.

Steely Dan’s “Deacon Blues” is another contrast. All the elements fit just so: the precise beat of the drums of Bernard “Pretty” Purdie, the shimmering electric piano of Victor Feldman, the dueling jazz guitars of Larry Carlton and Lee Ritenour, and the smoky tenor saxophone solo by Pete Christlieb. There is a studied grit straight out of the New Hollywood. Deacon is an amalgam of Elliott Gould’s bewildered Marlowe in Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye and Gene Hackman’s saxophone-playing Henry Caul in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation.

Hotel California offers nothing of this sort. Perhaps the concerted effort to create a product that is almost entirely synthetic in its effect inspires its own type of admiration, but listening to it only offered me limited epiphanies about the Eagles.

The producer of Hotel California, Bill Syzymcyk, had been helming the Eagles’ records since 1974’s On the Border, where he was co-credited with Glyn Johns. Tim credits Syzymcyk with setting the Eagles into mega stardom, similar, if fleetingly, to how Phil Spector shot the Righteous Brothers to the top of the charts with “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’.” The comparison is intriguing, but not one which I would co-sign. Casting aside the deeply problematic life of Spector, Bill Medley and Bobby Hatfield had a feel that eluded Frey and Henley. I’ll take Hatfield’s passionate “Ebb Tide” or the Medley-produced “(You’re My) Soul and Inspiration,” especially the first 20 seconds or so (proof that they gained something substantial from Spector), over, for example, the cold and clinical “Wasted Time,” Hotel California’s big power ballad, any day of the week.

The title song is the album’s first big statement. It strikes me as particularly prescient of this age of digital doom, particularly in the voices that are heard but never seen, as well as the woman with whom the protagonist dances and who offers the bon mot, “we are all just prisoners of our devices.” Hear that and wonder what role the Eagles played in today’s panic over our creative future. I’m not sure, however, if this is what the group had in mind here.

Tim captures well the unshakable feeling that the Eagles weren’t so much a band as “a corporation” and that they were fueled on—yes, that word again—cynicism. I may not be as cutting in my vitriol on this point—as I said earlier, I wasn’t there when the Eagles peaked—but that unshakeable feeling of rock-by-committee gets my back up just a bit.

It’s hard to feel otherwise when the vibe is oh-so-serious. Take the song that follows “Hotel California”: “New Kid in Town.” Tim is right that the song is unburdened by mirth. But shouldn’t a song about an outsider who used to be an insider have a twinge of the romance of the loner instead of, as Tim writes, confidence and swagger? Shouldn’t it have some of the touch of something like “Good Time Charlie’s Got the Blues,” cut four years earlier by Danny O’Keefe and covered almost immediately by Elvis Presley who tellingly omitted the lines, “I’ve got my pills to ease the pain / I can’t find a thing to ease the rain”? That song aches. “New Kid of Town” barely pinches a nerve.

And what about Fleetwood Mac’s bouncy “You Make Loving Fun,” the obverse of “New Kid in Town”? Christine McVie writes and sings about her very real new lover as her ex-husband John McVie both endures the indignity of having to play on his relationship’s musical epitaph and elevates it with his lock-step bass line—dig how he lets a note ring out as his ex-wife sings, “I do believe in miracles.”

Randy Meisner’s “Try and Love Again” gets close to that song’s authentic feeling and back to a version of the Eagles when their sweet, C-suite sound was something approximating a strength. There’s some real passion here—Meisner’s vocal in particular has a force against the beat. The supporting harmonies on the main refrain leaven it and the effect adds poignancy and heft. Tim makes no mention of it, but to me, it's the unsung highlight of Hotel California. What then to make that Meisner, the last vestige of the early Eagles, would soon be replaced by Timothy B. Schmidt? Schmidt is still with the group but then so is Joe Walsh.

Like Tim, my ears perk up when Walsh takes centre stage. Of all the virtues of “Life in the Fast Lane,” the one that sticks out most to me is its smirking irony which has always been part of Walsh’s persona (consider the killer couplet from “Life’s Been Good”: “my Maserati does one-eighty-five / I lost my licence, now I don’t drive”) that must have seemed at the time, and continues to be, anathema to everything the Eagles stood for. It offers a blessed respite, as does the one-two of “Pretty Maids in a Row” and the aforementioned “Try and Love Again,” before Hotel California’s closer, “The Last Resort.”

Irony is here again but only unintentionally. Purportedly the grand statement of what happens, as Joni Mitchell once put it, when you “[pave] paradise and put up a parking lot,” it strikes me as the summing up of the experience of listening to the Eagles at their most earnest which was, let’s face it, almost all of the time. The slow, deliberate vocal by Henley rolling out his great tale is its own kind of tedium. The final lines of “they call it paradise / I don’t know why / you call someplace paradise / kiss it goodbye” are more on the nose than Henley could have ever imagined.

It calls to mind when he inducted Randy Newman into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2013. In the midst of his stentorian speech, he mused how Newman is defined by two songs: “Short People” and “I Love L.A.” Someone then yelled out “we love it,” and Henley, without missing a beat, quipped, “we do, took me an hour-and-a-half to get here. I love it.” That’s the kind of irreverence I vibe with, and indeed, Newman’s sarcastic “I Love L.A.” says what Henley tries to in “The Last Resort” far better. Now it’s unfair to slag Henley for not writing like Newman but it certainly points to the ultimate reason why the Eagles escape me. It’s not exactly cynicism but the result of when you take yourself way too seriously.

—Robert Gilbert, from Listening Sessions

Subscribe to Listening Sessions

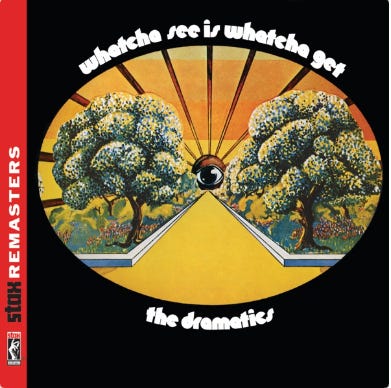

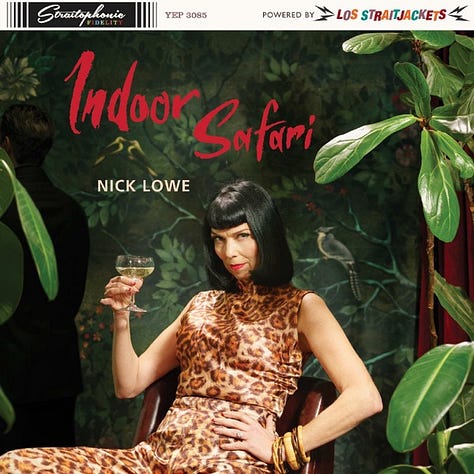

playlist of the month

July 2024 riley rock trailmix: advance singles from Nick Lowe, Annie Bosko and Dwight Yoakam, we’re all watching that Stax doc and wondering where the Staple Singers fit in (and where’s Jonathan Gould?), some Kpop a friend recommends, and Beck comes up as Scott Pilgrim saves the world.

noises off

Raid the archives for more on Joe Walsh before the Eagles, and his choice Ravel quote, Taylor Swift’s Multiplex (“Now excuse me while I stick pins in my El*n Musk doll while listening to my AI software read Streisand’s Deluxe Winnebago memoir in the voice of Kermit the Frog…”), and Rob Sheffield’s Solo Beatles List, rejoined, now with comments (from Jeremy Shatan).

riley rock index: obits, bylines, youtube finds, reference sites, pinterest, beacons.ai, random deep link

Great article. Lindsey Buckingham still goes to a pizza place a short walk from my house. Along with Steve Wozniak. I don't know if they know each other.

Anyhow, the great thing about Hotel California is, you can recognize it by the first chord and immediately change the station on the radio. Faux LA angst, and "cynical" pretty well describes it.

The thing about Hotel California, Aja, and Rumours is they gave us punk rock