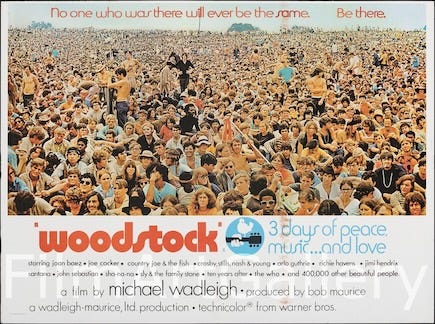

A few years ago we celebrated the 50th anniversary of Woodstock through a PBS documentary, which felt almost as toadying as “Disney Presents the Beatles.” But the “real” Woodstock documentary and soundtrack, its mythical consumer objects, arrived 55 years ago this month. Ellen Willis called this product a “great public relations coup.” That summer of 1970 also witnessed Gimme Shelter, and Let it Be. Michael Wadleigh’s splashy, immersive film amplified hippie style and brought new TV gigs for John Sebastian; Joan Baez dutifully sang “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” over 25 years later at Newport. Sly Stone vied with the Who and Hendrix for epic runaway energy. And in 1989, the Boston Phoenix ran this 20-year commemoration:

WOODSTOCK'S NAIVE, COUNTER-CULTURAL innocence has come to signify nearly everything it set out to remedy. What it represented as culture was a generation's self-identity; what it represented as music was a coming of age.

But what was once culturally significant has now become just another commercial fact of life, another commodity to be bought and sold. The event bespeaks both today's arena-rock standards and the increasing distance between artists and their audience. Acts like Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and the Who, which had made Monterey debuts two years earlier, reappeared at Woodstock as professional titans of rock theatrics.

As captured on record and film, the August 1969 event bridges rock utopianism and capitalist opportunism. Record executives mingled backstage with dollar signs in their eyes, ogling a crowd that wasn't chanting "Revolution." If you watched a recent MTV broadcast broken up with beer ads and an MTV logo blazoned across idyllic shots of skinny-dipping hippies, you might have begun to realize just how skillfully corporate interests have exploited the event that momentarily charmed commercialism into trippy submission.

All this becomes glaringly apparent as you watch Michael Wadleigh's Academy Award-winning documentary, Woodstock, which has been re-released in widescreen form on Warners Home Video. Edited with the help of Martin Scorsese's ears, it's the first respectable rock concert film, the first to give something back to its subject.

The film's rhythmic cross-cuts and split-screen simultaneity allow rock's jumpy contradictions to ring through; it makes D.A. Pennebaker's Monterey Pop look like a high-school talent show. The best performances here argue that the festival never really set out to remedy much at all—its intentions never were all that high and lofty.

Scorsese was apprenticing for The Last Waltz, the Band's epic farewell concert at San Fransisco’s Winterland five years later, and despite the quaintness of hippie language, clothing, hairstyles, and self-congratulatory airs, the music still tells a bigger story than the event. The film's rhythmic cross-cuts and split-screen simultaneity allow rock's jumpy contradictions to ring through; it makes D.A. Pennebaker's Monterey Pop look like a high-school talent show. The best performances here argue that the festival never really set out to remedy much at all—its intentions never were all that high and lofty.

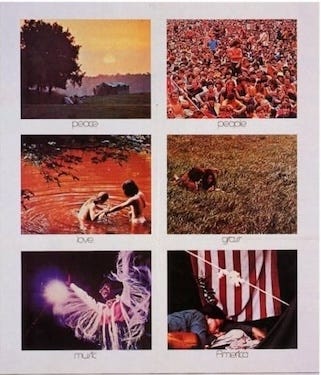

The opening sequences are the most portentous, a kind of New Eden overrun by electronics. To the sound of Crosby, Stills & Nash singing "Long Time Gone," we see longhairs mounting horses, mingling with cows, riding tractors, driving cars—even a moon buggy whirs past. This promenade of vehicles builds to a cherry picker and a hilarious barn-raising shot of the peaceniks erecting their stage, the altar for their tribal gathering. As Michael Lang, a festival promoter, takes to a green field atop his motorcycle, you can tell this cinematic heavy-handedness has to do with the beatific way the presenters want to portray themselves: at peace with nature, at one with technology.

After that, the film is only intermittently disruptive, even though it distorts the actual sequence of acts for what seems an arbitrary hierarchy of players. (Why do the Who follow Joan Baez? What is Joe Cocker's Saturday-afternoon set doing after Sha Na Na's Monday-morning jog?) Richie Havens took the stage Friday afternoon after an unknown Boston band, Quill. Because Havens was a symbol of folk's civil-rights connections, the huge close-ups give his stern face and gospel growl a larger-than-life magnanimity, as though the filmmakers wanted his nostrils to define a generation. (Remember, covering the Beatles' "Here Comes the Sun" was this man's only Top 40 hit.) He's followed by the unbearably pious Joan Baez, who along with the dissonant Crosby, Stills & Nash and the sky-high grin of John Sebastian could fool you into thinking that folkies still held their own with acid rock. Not true: the radio was blaring "Honky Tonk Woman" all summer, and Led Zeppelin's "Whole Lotta Love" was on its way.

The split-screen imagery works to convey the private moments that peek through the enormity of the crowd, but it functions best when it works in tandem with the music. As the Who gain on "See Me, Feel Me" (the finale from Tommy) and pummel through Eddie Cochran's "Summertime Blues," Roger Daltrey's golden curls and dangling leather fringe seem as daring as any Jagger taunt. Pete Townshend leaps and sprints, and his guitar arrests the music from his fingers before he unplugs the instrument from his amp and lofts it unceremoniously into the front row; the triple-screen angles only intensify the band's violent interactions. And there are some sly visual jokes: Sha Na Na storm the screen as the punch line to hairy close-ups of a visiting Indian meditation master; the bouncing-ball sing-along to Country Joe McDonald's stinging Vietnam-recruitment satire ("Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-To-Die Rag") still gets audiences to join in. (Without the surrounding context of the draft, the ballooning casualties, and Nixon’s escalations, the song sounds almost innocent…)

The movie is as famous for who it omits as for who it includes: Janis Joplin, the Band, the Grateful Dead (who played a notoriously weak set), Creedence Clearwater Revival, Jefferson Airplane, and Mountain, not to mention a large portion of Jimi Hendrix's playing (now an essential standalone). And some sequences lapse into pure cliché. Arlo Guthrie's star may have been on the rise (toward Alice's Restaurant), but his "Comin' into Los Angeles" is merely backdrop for the obligatory toke-up tableau. Guthrie's presence is overshadowed by the specter of Bob Dylan, who actually lived nearby at the time and performed at the Isle of Wight Festival in England later that same month.

Still, this mishmash of musical intentions explains why Woodstock has become all things to all people. Politicos point to its summer-of-the-moonwalk "global consciousness," and the crowd's wafting pacifism placates the racial violence of Gimme Shelter's Altamont as if this were a neatly tailored media script. Aesthetes, on the other hand, boast about the music's stylistic range and diversity. Although there were more blacks and Hispanics on stage than in the crowd, the film climaxes with Santana's rhythmic potboiler "Soul Sacrifice," the sizzling soul-funk polemics of Sly and the Family Stone, Jimi Hendrix's cosmic retooling of the national anthem. (Hendrix's languid blues jam makes the perfect clean-up soundtrack.) That this music holds up at all is a miracle, given some of the bullshit pretensions it sprang from, and condoned.

In the end, it's the contradictions that keep the music alive and make the film worth seeing again. The closing-credit sequence, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's version of Joni Mitchell's "Woodstock," became the festival's self-benediction. ("I dreamed I saw the bomber death planes riding shotgun in the sky…"), even though Mitchell herself sat stuck in a hotel room. The audience's lust for heroes is not lost on any of these musicians, who amble through the proceedings with bemused grins; they seem to know nothing will ever be the same. As John Sebastian told Life magazine recently, "All us entertainers have a good giggle when all these reunions come around. You could have caught us for half price last year."

MORE

You can get all boxy with it, or go for this 1969 Complete Bootleg project in flac format on the Internet Archive. Youtube bulges with choices, including this selection of the 40th Anniversary edition of Woodstock bonus features, a remastered version of the Who’s set, a playlist compilation of Jimi Hendrix’s set, and another of the Creedence set.

noises off

From the archives: a chat with Mood Machine author Liz Pelly; Gimme Shelter’s Altamont as “prophecy and sinkhole”; and more on the Who’s 1989 “comeback” tour

“I joked that I was surprised to see him in a tan suit because if he wore that out, it would be perceived as un-Führer-like.”—“My Dinner with Adolf,” by Larry David

riley rock index: obits, bylines, youtube finds, reference sites, pinterest, beacons.ai, random deep link

Nice piece, Tim. It remains one of my favorite docs, despite the exclusion of a band or two. The Dead’s weak set should always have an asterisk denoting the steady stream of electrical current they were receiving from the faulty stage ground. Thanks for taking me back to this one. I just added it to the weekend queue.