[In What They Heard, author Luke Meddings maps some detailed 1963-1968 timelines of record releases and how songwriters bounced off of one another. The Beatles, the Beach Boys, and Bob Dylan (and the Byrds, the Stones, and the Kinks) all seemed attuned to a higher frequency alive in the music, and kept piling on one another with new sounds. Meddings finds so many interesting hidden ideas here that the music springs up anew, and you start to hear previously invisible connections. I talked to him from his home in London… This transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.]

Tim Riley: Hello there. Welcome. Which part of England are you in? Luke?

Luke Meddings: I'm in London.

Tim Riley: Well, I'm in Boston congratulations on this wonderful book. I love this book so much. I was so excited to talk to you about it.

Thank You so much. I'm glad you liked it.

Tim Riley: Just a lovely idea for a book and a lot of lovely descriptions in here. I like your very embracing and, suggestive and, just very workable idea for a definition of rock and roll, which I think is really hard.

I love it. So gimme an idea of your background and is this your first book?

Luke Meddings: My background is in terms of my sort of day job work. I've done market research, I've done a bit of journalism and I've also done education and I've published two books.

You know, Neil said, you wanna have a, a crack at this as a book tracing how artists in the sixties inspired each other, but also quite specifically. And that's what led to the timelines when things happened. Because I think, you know, certainly when I, when we were having those chats, I, I, I had a good sense of when things happened.

And obviously what happened in the mid sixties is easier to trace than what was happening in Memphis in the early fifties. It's still not possible to say for sure who influenced who and exactly when that happened, but it's a lot of fun trying to figure it out.

And then it sort of comes full circle when the Beatles are, are kind of playing through a whole bunch of rock and roll covers during the let it be B sessions.

Tim Riley: There's always this problem with this period in rock and roll between, you know, when, when say Buddy Holly dies and the emergence of the Beatles and it always gets called fallow.

And us critics know it's always, it's very rich. And I'm wondering where Dylan fell for that cliche idea that rock and roll was dead for a while in the middle.

…sometimes you can hear Paul McCartney saying, “well we were just a rock and roll band.'' And you sort of think, okay, well that's, that's the biggest, humble brag that you've ever heard…

Luke Meddings: Yeah, it's so interesting, isn't it, because it's sort of everything that happens af sort of between 1959 and 1962 and there's so much of it and you know, that's when Motown starts and that's when the folk revival starts.

All sorts of interesting things are happening. Blending those influences with rock and roll is what gives you some of this, the, the kinda seeds, the, the raw material for the, the new music that they make in the sixties. But yeah, it's, , it's a real myth. And the Beatles completely sort of, reinforced it.

I think it must be partly that they invested so strongly in the music and the personality. And the music and the personalities is incredibly intertwined in the kind of peak rock and roll in the mid '50s, when Elvis goes into the army and comes back singing ballads, when Little Richard throws his rings over the Sydney Harbor Bridge, when Joe E. Lewis kind of gets disgraced. I think they must have felt it kind of viscerally, you know, personally. The Beatles talk, you know, in the interviews, they keep saying, ''we're just playing rock'n'roll.'' You know, so sometimes you can hear Paul McCartney saying, ''well we were just a rock and roll band.''

And you sort of think, okay, well that's, that's the biggest, humble brag that you've ever heard. So much happens in that supposedly fallow period…

MORE

What They Heard: How The Beatles, Beach Boys and Bob Dylan Listened to Each Other and Changed Music Forever, by Luke Meddings (Weatherglass Books, 2021)

“Roll Over Beethoven,” by James Cook in TLS

Book review by Amy Hughes in beatles-freak.com

Alan Dearling in The International Times

Luke Meddings on Joe Wisbey’s Beatles Books podcast

Last Sunday at Marlboro…

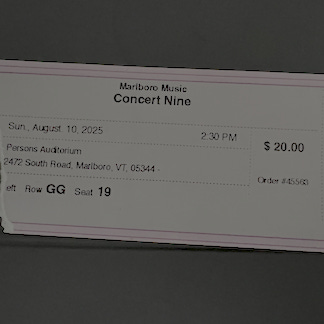

AFTER YEARS OF admiring the recordings and dreaming about an idyllic chamber music haven, the Marlboro Music Festival finally came into view last week for a program of Mozart, Schumann, and Bartok. Marlboro, Vermont, lies roughly two hours north-west from Boston, and the weather complied: Persons Auditorium, built in 1962, seats around 500 people, held a typical rapt audience last Sunday. The Mozart Horn Quintet in E-flat Major K407 had an understated spark, with runs and trills from Carys Sutherland that spilled from her instrument with great ease and humor. The Schumann Phantasiestücke (1842) works as piano trio, although even at opus 88, it hasn't entered the mainstream repertoire yet (along with Reena Esmail’s setting of Wendell Berry’s poem ''Who Makes a Clearing,'' this counted as its first Marlboro performance). It suggested Schumann had internalized both percipient late Beethoven and deliriously melodic late Schubert to combine beauty with regret for the most forgiving mix. Professional standards turned secondary to the inner meanings and subtextual nuances; you felt as if Schumann had whispered secrets into these players' imaginations.

After intermission came Esmail, and then Bartok's Fourth String Quartet (1928), with Sara Bitlloch, Angela Sin Ying Chan, Laura Liu, and Annie Jacobs-Perkins. This one-off group tantalized and scolded by turns, making Bartok sound both modern and ancient, intimate and cosmic. How is it that these jagged rhythms still sound stunning a century later? Where did Bartok find his inimitable colors, unlike any other in the quartet repertoire, and set them loose to such provocative effects? How does a composer set loose such taunts with a heart so big it seems to overwhelm even the spiky, daunting pizzicato third movement? We wandered back out into the fresh country air, marveled at falling into informal conversations about Bartok's Third Piano concerto, and how the Fibonacci series served as this composer’s ideal organizing framework without restricting the music's spontaneity.

Tickets sold for a scathingly modest $20; get thee to a classical music retreat to fill up on hope for world. The ghosts in Vermont (Pablo Casals, Rudolf Serkin, the Guarneri Quartet) still sing through today's players.

Horn Quintet in E-Flat Major, K. 407 (1782), by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, on Brahms, Ligeti, and Others: Horn Trios (Martin Owen, Francesca Dego, Allessandro Taverna, 2024)

Phantasiestücke, 0pus 88, by Robert Schumann (Gautier Capuçon, Martha Argerich & Renaud Capuçon, 2010)

Six String Quartets, by Béla Bartók (Hungarian String Quartet, 1962)

Marlboro Recording Society, Marlboro Festival Orchestra streaming catalog

noises off

From the archives: we’re still One Nation Under Groove, and the funk can’t save us but it helps; more on Brian Wilson, and those Taboo Sex Jingles can’t save Babygirl’s cringe

South Korean pianist Hieyon Choi, now at the Peabody Institute of Music in Baltimore, has released her complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas (“Testament”) on Decca Korea, streaming at the link

riley rock index: music’s metaportal, with obits, bylines, youtube finds, reference sites, pinterest, beacons.ai, and a random deep link